Creativity is Life

Or: Hildegard of Bingen explains the name of this Substack

In my previous post, I reflected on watching Wes Anderson movies in the convent and becoming obsessed with creative collaboration. Connection, relationship: there is something ontological about how connection leads to creativity. The more connected I am, the more creativity flows. This is so much in opposition to some temptations of the artist to withdraw. (Nothing against solitude, though.)

But there’s something more. It’s not only about our connections with each other. There’s a connectedness that precedes and grounds our human connections—a connectedness at the base, the source. It’s the source of life itself. And Hildegard of Bingen can illustrate this point because she is one of the most fruitful artists (composers/mystics/writers/doctors/preachers) who ever lived.

Hildegard has mesmerized me for a long time because her fruitfulness is explosive. Let me tell you—this woman worked in at least six genres! Between her birth in 1098 and death in 1179, Hildegard:

wrote two books of mystical visions complete with visuals (illuminations)

founded a monastery

healed people as a medical doctor/herbalist and wrote two books on medicine and science (from her medieval perspective)

composed music

wrote plays

completed preaching tours along the Rhine River (she is sometimes called the first woman to go on a preaching tour)

offered counsel and/or critical feedback to Emperor Frederick Barbarossa, King Henry II, and multiple popes

The strangeness of her medieval worldview attracts me. Enter Hildegard’s world and the wind takes on a lobster face, stars flame out like anemones, heads inter-nest in each other; scientific work reads like poetry (“in a stone there is moist greenness, palpable strength and red-burning fire”); and ill people (the gouty, to be precise) are admonished hold a sapphire in their mouth.

But Hildegard’s medieval strangeness is grounded by her compassion. The detail I treasure most from Hildegard’s life is her insistence upon burying an excommunicated youth in consecrated earth in defiance of ecclesiastical authorities. (The bishop punished the sisters by forbidding them to pray together or sing, an extreme punishment for them.) I feel close to Hildegard when I connect with earth and my body by making yarrow salve or cooking with fennel, one of her highly-recommended foods. (Spelt, almonds, and a sugarless spice cookie also earn her approval.)

So what made this woman so creative, so fruitful, so…explosive?

Hildegard believed in the divine embrace.

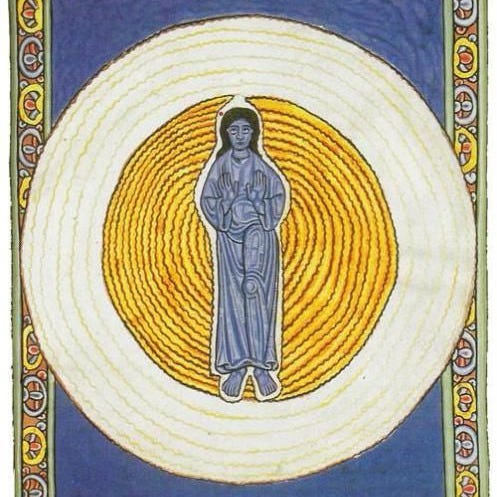

Consider her Sapphire Blue Man from Book II, Vision 2 of Scivias. (I bought a metal retablo with this image on it over ten years ago and hung it in my first classroom.) The image shows a human stepping forward, hands lifted in blessing, with a sapphire blue body and garments. He is encased in a golden light, which is itself surrounded by a whiter light.

The man is surrounded, held, encased in something not himself—in two such protective layers! When I showed this image to my fifth grade class years ago, one of my students said that it looked like an egg, and the metaphor is very apt. The man is incubated—protected—one with this warm light. Yet it’s unclear from the image alone whether the light encases the man, or whether the light emanates from him. He is also carrier of the light.

This is Hildegard’s vision of the holy Trinity. But what would it mean if we allowed ourselves to stand in place of the sapphire blue man: surrounded, supported, held by a power beyond ourselves?

There’s a resonance between this image and her vision of the cosmos shaped as an egg from Scivias Book I, Vision 3. The vision shows an outer layer of fire, a dark layer (‘dark membrane’), a layer with ‘bright spheres,’ and then a ‘sandy ball,’ the earth, with a great mountain on it.1

So, the image shows the universe. It contains familiar elements such as stars and ether as well as medieval details like the dark membrane and the fire. But is it only the cosmos? What does this vision mean for Hildegard?

In a stunning move, Hildegard explains that the large egg-shaped form represents the Divine Creator. Humanity on the earth (the figure in the center) is completely held within the divine energy. It’s difficult for me not to meditate on this image as representative of God’s womb with all of creation as a beloved child.

How did Hildegard get to this point? What informed her perspective? How did it all begin for her? Not unlike the Man in Sapphire Blue, Hildegard had an experience of encountering divine light. Hildegard’s creative-spiritual awakening was an encounter.

When I was forty-two years and seven months old, a burning light of tremendous brightness coming from heaven poured into my entire mind. Like a flame that does not burn but enkindles, it inflamed my entire heart and my entire breast, just like the sun that warms an object with its rays.

Hildegard is receiving the self-communication of a divine Person who is saying to her:

I am here.

I surround you.

Hildegard then sees Love’s fire in everything living.

Coda:

In my prayer, once, I was in a dungeon—specifically, where young St. Francis is imprisoned by his father, who is angered by Francis’s squandering his cloth wares on the poor. In my prayer Hildegard enters, unties me, and lets me go.

In Francesco’s story, this episode is the penultimate event before he “becomes” St. Francis. He goes to the town square— throws off all his clothing—renounces his inheritance—breaks with his old life as a merchant and knight and man about town. Francis then takes up his authentic life: he lives among people who are unhoused, cares for lepers, proclaims peace, and spreads the good news of the kingdom.

This was a powerful prayer experience for me, and I share it with all of you in the hope that it might bless you, too.

What did I take from it?

Hildegard—her connectedness, her creativity—will lead you to freedom.

This post is dedicated to my sister Rachel, my Hildegard buddy. Our Hildegard book club has been one of the most special creative collaborations I’ve been able to share!

Atherton, Mark. Section 20. Hildegard of Bingen: Selected Writings. http://faculty.las.illinois.edu/rrushing/241/ewExternalFiles/Hildegard.pdf